The days passed, the waves kept pumping, and before I knew it, two weeks had slipped away. I could spend a lifetime in the little town by the river, surfing with my friends, watching throngs of birds come to feed and nest, peeling sunshine-colored mangoes, sticky and sweet. Maybe someday I will shed the skin of my old life and return here, reborn. That is what I told myself in consolation whenever I thought about leaving.

There is never a good time to leave something that you love from the deepest part of yourself. But some times are better than others. The road to my next stop, La Ticla, had been closed for nearly 2 weeks, due to a protest. Buses were not permitted to pass. Cars were stopped and let through intermittently. It was a good excuse to stay planted in the little town by the river. But then Flaco offered to take me to Ticla, and though I wasn’t ready to leave, I knew I would never be. So I went.

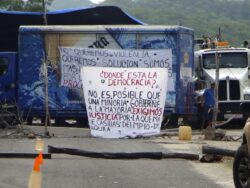

The highway approaching La Ticla was adorned with diminutive logs and orange cones which were shadowed by a semi-truck that bisected the road. Splashed with a bright blue advertisement for Corona Extra, the truck displayed a patch of bright white canvas, strung up along its side, decorated carefully in hand painted letters:

NO QUEREMOS VIOLENCIA/WE DON’T WANT VIOLENCE

QUEREMOS SOLUCION/WE WANT A SOLUTION

SOMOS MAS DE 100 PUEBLOS UNIDOS/WE ARE MORE THAN 100 TOWNS UNITED

In front of the semi-truck, slender branches were propped upright with stones. A strained rope was stretched between them, sagging under the weight of tired hope like a hunchback bent over in a field. Another patch of canvas, another brave statement in proud capitals:

DONDE ESTA LA DEMOCRACIA/WHERE IS THE DEMOCRACY

NO ES POSIBLE QUE UNA MINORIA/IT IS NOT POSSIBLE FOR THE MINORITY

GOBIERNE A LA MAYORIA/GOVERNMENT IS THE MAJORITY

EXIGIMOS JUSTICIA/WE DEMAND JUSTICE

Weathered men slumped in hammocks amongst the brush on the roadside, shaded by rough, thorny bushes and stiff, starched cowboy hats. Others strode purposefully along the roadblocks, their expressions set in grim, proud lines.

Flaco pulled in behind another car and shifted into park. A man approached and said we needed to wait a few minutes, but eventually we would be permitted to pass. A roadside vendor sold us homemade tamales made from sweet young corn. He served us from the back of his truck, storing his goods in two old tires, unwrapping the tamales from their husks, topping them with salsa and cream.

We went for a walk among the papaya groves, the trees bending under the burden of ripe fruit. As minutes turned into hours, we sat on the tailgate of the truck and played Gin Rummy, keeping score on the back of a travel receipt. The end of the game was decided when the roadblock opened. Flaco won.

We pulled into Ticla, a tiny town with two small stores that occasionally have beer and bread and 3-4 types of produce; three sporadic restaurants that are open sometimes, when they have nothing else to do. We bought onion, tomato, chiles and lime for poor man’s guacamole; surfed the cobblestone beach break among copulating turtles and walked along the muddy banks of the river as birds gathered and fisherman cast their nets. An old woman limped along with a bucket perched on her head. She sold us fish empanadas and chicken tamales, which we ate with our poor man’s guacamole for lunch.

We drove to a neighboring beach so that Flaco could fish. It was wide, vast, and deserted, with fine powdered sand and large islands of rocks which reminded me of home. The sand squeaked noisily under Flaco’s feet as he walked. He told me it was a special characteristic of the beach, something it was known for. I shuffled and stepped, but try as I might, I couldn’t produce the same sounds with my own gait.

While Flaco fished, I went freediving beyond the massive castles of rock guarded by moats of ocean. I looked back once and saw him holding a turtle; then again as he pounced on a small sand shark. He is half Mexican, half indigenous. I suspected that this was one of his childhood games, catch and release. After awhile, he swam out and we climbed the rock, eye level with the mountains, in the middle of the sea. An ecosystem of grasses, plants, insects, birds and marine animals had made its life on this tiny island. A remnant of a prehistoric time, preserved like a miniature morsel of world in a snow globe; shake it and watch as it becomes animated with moving life.

Flaco returned home to Michoacán and I continued on to Pascuales, catching a ride from Jorge and Mina. Jorge was from San Pedro, near Sayulita, and it turned out that Javier, whom I had met in Salina Cruz, was his boss. Mexico is a big country, but the surfing community is small, tight, connected. We passed through a second roadblock to the north of La Ticla, as hundreds of townspeople watched from hammocks strung up on the side of the road.

When I arrived in Pascuales, I ran into Paulo, whom I had met at the small town by the river in Michoacan. He had told me that he lived in La Ticla. We sat down together so that I could hear his story.

Paulo grew up in El Real, a small beach town adjacent to Pascuales, near the larger city of Tecoman. When he was five years old, he received a gift of a boogie board, which he used as a pool toy until the day that he saw a TV commercial, by chance, that featured a boogie board in its intended use, on the waves. “From that moment, my life changed,” Paulo said. He began taking the boogie board into the ocean and learning to catch waves, standing on it as if it were a surfboard. Later, his brother got a proper surfboard, and they shared, taking turns.

One day when Paulo was about 12 years old, he and a few of his friends decided to go in search of other waves, outside of town. They ditched school with money in their pockets and surfboards under their arms, thumbs out on the side of the road, begging rides from cars passing by. They ended up in La Ticla, which at the time was nothing more than a dirt road leaking out from under the ramshackle highway, travelled by horses and donkeys rather than cars.

As the group made their way down to the beach, they were surprised to see other surfers, an indigenous boy about their age named David, out with his brothers and friends. David and Paulo became fast friends, and David’s family invited the group to stay at their home for the night. David’s parents, Don Ramiro and Doña Seferina, put the boys up for three days, cooking them eggs, beans, fish and iguanas.

After a few days, the group returned to El Real, but Paulo travelled back to Ticla most weekends and school vacations, every chance he got. He began to think of David’s family as his second family, calling Don Ramiro tía, or uncle, and Doña Seferina tía, or aunt. “That family changed my life,” Paulo reminisced. Don Ramiro showed him how to live in the jungle, catch fish, dig for mussels in the river, and hunt iguanas.

The year was 1995, and there was no electricity in Ticla, no lights or television. The indigenous people still continued to live according to traditional ways, as they had for many years. They grew maize, or corn, and made tortillas, raising their own animals for eggs and meat. Paulo’s uncle, Don Ramiro would go up the road with five donkeys to collect wood, which the family used to cook over an open fire. “It was the best paradise for me,” Paulo remembers.

Another important aspect of life in La Ticla at the time was marijuana, which the townspeople cultivated in the surrounding mountains. They used it for medicinal purposes, processing it into a topical salve for aches and muscular ailments. They also smoked it for relaxation and recreation.

In the mid-90s, La Ticla was experiencing the early ripples of globalization, as surfers and hippies began to trickle in from the states, looking for novel waves and an authentic experience. And inevitably, they also wanted weed. At a time when 10 or 20 pesos ($1-2 USD) was a lot of money to an indigenous family in La Ticla, tourists were paying about 300 pesos ($30 USD) per kilo for marijuana. This income meant that families could buy meat, clothes, and building supplies; have big fiestas, or parties, for everyone in the town. “Those were the good times,” Paulo recounts.

After staying intermittently with David and his family for several years, Paulo moved to La Ticla permanently when he was 17. Though he is Mexican by blood, Paulo cannot buy land there due to the fact that he is not indigenous. Even if he were to marry a girl from La Ticla, he still could not buy land. To this day, land can only be owned by people who are indigenous to La Ticla, and ownership is carried primarily by the men. Tradition dictates that if a man marries a girl from another pueblo, he must bring her to live in his own hometown. There are no papers that dictate eligibility. As Paulo says, “The people just know.”

So Paulo lived with David and his family, and opened a restaurant and hostel with David’s brother, Gustavo. In 2007, Paulo noticed that La Ticla was beginning to change, rapidly. In the preceding years, government affairs had begun to exert influence on the self-governing town. Opposing political parties attempted to buy the loyalty of the townspeople by giving out free clothing and food. “One party would give away something free and the next day, another party would come and try to top it,” Paulo recounts.

At first, government influence was well received. It brought electricity to La Ticla, and opened people’s minds to the possibility of a more modern and lucrative life. But then the government brought in its own police under the guise of maintaining order. A town that was used to administering its own affairs was infiltrated by outsiders who sought to control every aspect of their lives. Police came in from the big cities and bullied the townspeople with harsh words and guns, extorted money from them. “All the cabrones (motherfuckers) came from Mexico City,” Paulo laments. Families were required to pay 100-200 pesos per month to the new police, under threat of violence if they failed to do so. They were also forbidden to sell marijuana to the tourists; this business was taken over by a government-backed cartel.

Why would the government do such things? I was confused about the purpose of the terrorizing. Paulo believes that it has something to do with the treasures in the mountains surrounding La Ticla. Deep in the rolling hills lie vast reserves of carbon, silver, jade, and marble. The government oversees the mining of these commodities, and employs indigenous people to perform the hard labor required for extraction. “The government doesn’t want to pay for what it is taking from the mountains, or pay the workers a fair wage,” Paulo speculates. And so the government spreads fear like pesticide, trying to weaken seeds of uprising before they have time to sprout.

But a people born of the jungle, made of flesh and bone and nerve and sinew as tough the animals they hunt, will not lie down easily in defeat. In 2013, vigilante groups began to organize, which led to shoot outs between local forces and the Mexican army. The violence has continued to culminate in a gruesome circus of mysterious acts with shadowy perpetrators. In 2014, a group of 43 students was captured during a protest, their bodies never found. The families of the students blame the Mexican army for the deaths since reports surfaced that a group of soldiers had run into them just before they disappeared. Earlier this year, Cemeí Verdía, the head of the rural police in the local indigenous Nahua community, was arrested, and citizens organized a roadblock in the Aquila municipality last month to protest. Government soldiers swiftly arrived to disperse the roadblock, inadvertently shooting and killing an innocent 12 year old as he tried to flee. At a press conference, General Felipe Gurrola, who is in charge of security in Michoacán, denied the allegation, but citizens maintain that they could clearly see Mexican Army insignias emblazoned on the soldiers’ vests, and that the soldiers fired directly into the crowd.(1)

This is the history that is the lump in the throat of La Ticla, the story that is written on the hard grim lines of the people’s faces, the burden that slumps the canvas of their signs and strains the muscles of their hearts. Waiting at the roadblock; talking with Paulo into the night; thinking of the indigenous people and their brave, proud struggle, their will and defiance and stubborn grit; I too feel a lump in my throat. It is something like pride, something like hope, something like admiration. I am glad that there are people in this world who still catch fish, dig for mussels in the river, and hunt iguanas; who cast their frayed nets in unison, hoping for peace.

1. Death of child in Michoacán throws state security efforts into question. Luis Pablo Beauregard. El Pais. 27 July 2015. http://elpais.com/elpais/2015/07/27/inenglish/1438002383_611941.html

The mayor of Iguala and his wife were arrested for the kidnapping of the 43 students. Iguala’s police chief remains a fugitive. Sad story but beautifully told, Aloe!

I love this so much.

My day is complete now…a wonderful new blog from you. Beautiful and sooo interesting.

Luya sooo much, Nana